The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress on October 20, 1774, in Philadelphia. It aimed to address the colonies' grievances, particularly the Intolerable Acts, through a trade boycott against British merchants. The "non-importation, non-consumption, non-exportation" agreement, suggested by Richard Henry Lee and based on the 1769 Virginia Association initiated by George Washington, began with a pledge of loyalty to King George III and banned British imports starting December 1, 1774. The boycott caused a sharp decline in trade with Britain, which retaliated with the New England Restraining Act. The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775 rendered the boycott unnecessary. The Association demonstrated the colonies' collective will to act in their common interests and is considered a foundational moment in the creation of the union that would become the United States, as referenced by Abraham Lincoln in his 1861 inaugural address.

Twenty of the 53 signers also signed the Declaration of Independence.

Two of the signers eventually became Loyalists after the signing of The Declaration of Independence, and fled to Britain. They were Joseph Galloway and Isaac Low. One of the signers, Silas Deane, died under mysterious circumstances on his way back to Boston, and is buried in Deal, UK.

Thus far we have visited 36 of the 53 gravesites of these signers.

Recommended video: The Forgotten Foundational Document: The Articles of Association. by @TheHistoryGuyChannel.

Twenty of the 53 signers also signed the Declaration of Independence.

Two of the signers eventually became Loyalists after the signing of The Declaration of Independence, and fled to Britain. They were Joseph Galloway and Isaac Low. One of the signers, Silas Deane, died under mysterious circumstances on his way back to Boston, and is buried in Deal, UK.

Thus far we have visited 36 of the 53 gravesites of these signers.

Recommended video: The Forgotten Foundational Document: The Articles of Association. by @TheHistoryGuyChannel.

Name

DOB - DOD

Burial Location

Visited

Edward Biddle

1738 – 5 September 1779

Baltimore, MD

Simon Boerum

29 Feb 1724 – 11 July 1775

New York, NY

Stephen Crane

1709 – 1 July 1780

Elizabethtown, NJ

Thomas Cushing III

24 Mar 1725 – 28 Feb 1788

Boston, MA

John De Hart

25 July 1727 – 1 June 1795

Elizabeth, NJ

Silas Deane

4 Jan 1738 – 23 Sept 1789

Deal, UK

James Duane

6 Feb 1733 – 1 Feb 1797

Duanesburg, NY

Nathaniel Folsom

28 Sept 1726 – 26 May 1790

Exeter, NH

Joseph Galloway

1731 — 29 Aug 1803

Watford, UK

Thomas Johnson Jr.

14 Nov 1732 – 26 Oct 1819

Frederick, MD

William Livingston

30 Nov 1723 – 25 July 1790

Brooklyn, NY

Isaac Low

13 Apr 1735 – 25 July 1791

Cowes, UK

Thomas Mifflin

10 Jan 1744 – 20 Jan 1800

Lancaster, PA

Richard Smith

22 Mar 1735 – 17 Sept 1803

Natchez, MS

John Sullivan

17 Feb 1740 – 23 Jan 1795

Durham, NH

Matthew Tilghman

17 Feb 1718 – 4 May 1790

Claiborne, MD

Henry Wisner

1720 – 4 Mar 1790

Wallkill, NY

* Gravesite on Private Property

Historical Background

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia on October 20, 1774, as a response to the escalating American Revolution. The colonies aimed to apply economic pressure on Britain, hoping to force Parliament to address their grievances, particularly the repeal of the Intolerable Acts. The agreement outlined a "non-importation, non-consumption, non-exportation" policy that called for a boycott of British goods. The boycott, suggested by Richard Henry Lee and based on an earlier Virginia initiative by George Washington and George Mason, opened with a pledge of loyalty to King George III but blamed Parliament for the oppressive laws imposed on the colonies.

The Continental Association's ban on British imports began on December 1, 1774, significantly reducing trade with Britain. In response, the British passed the New England Restraining Act, further escalating tensions. However, the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775 overshadowed the need for the boycott. Despite this, the agreement represented the colonies' growing unity and resolve to act collectively in defense of their rights. Abraham Lincoln later recognized the adoption of the Association as a foundational moment in the formation of the United States, noting it as the origin of the Union in his first inaugural address in 1861.

Background

The Coercive Acts, passed by Parliament in 1774, aimed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party and restructure colonial administration. This led to the convening of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774, where delegates from twelve colonies met to coordinate a response. Leaders such as George Washington, John Adams, and Patrick Henry were present. The Congress rejected a plan of reconciliation with Britain, fearing it would acknowledge Parliament's right to regulate colonial trade and impose taxes. Many Americans saw the Coercive Acts as a threat to their liberties, sparking the call for economic boycotts.

The boycott idea gained traction in May 1774, when the Boston Town Meeting, led by Samuel Adams, passed a resolution urging a halt to trade with Britain until the Boston Port Act, one of the Coercive Acts, was repealed. Paul Revere played a key role in spreading this message. Congress soon endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, which advocated for an embargo on British trade and called for the colonies to organize militias. This cooperation among the colonies laid the groundwork for the Continental Association, adopted on October 20, 1774, to address the growing crisis.

Provisions

The Continental Association immediately banned British tea and, starting December 1, 1774, all imports from Britain, Ireland, and the British West Indies. If the Intolerable Acts were not repealed by September 10, 1775, the colonies would also stop exporting goods to these regions. Article 2 specifically banned ships involved in the slave trade. The agreement also addressed the potential scarcity of goods, restricting merchants from price gouging. Local committees of inspection were established to monitor compliance, and violators were publicly ostracized. The Association promoted frugality, discouraging extravagance in clothing and even setting guidelines for simple funeral observances.

Enforcement

The Continental Association went into effect on December 1, 1774. Compliance was largely enforced through local committees, which were effective in most colonies except Georgia, where the need for British protection from Native Americans hindered participation. Public pressure played a significant role in enforcing the boycott, with newspapers and social networks shaming those who violated the agreement. In some cases, direct action was taken, such as in Annapolis, Maryland, where a merchant chose to burn his ship rather than face the consequences of importing British goods. In areas where enforcement was difficult, some counties enacted price ceilings to discourage smuggling.

Effects

The boycott caused a dramatic drop in trade with Britain, and by early 1775, the local committees of safety had become de facto revolutionary governments in many colonies. The Continental Association forced colonists to take sides, with Patriots supporting the boycott and Loyalists opposing it. In South Carolina, for example, Patriots dominated coastal areas, while Loyalists were more prevalent in the backcountry. The Association also led to the development of new governmental structures that supervised revolutionary activities.

Britain responded by passing the New England Restraining Act, which restricted the colonies' ability to trade with anyone except Britain and the British West Indies. This act, along with other punitive measures, only intensified the conflict, eventually leading to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. Although the boycott ended with the war, the Continental Association's lasting impact was its demonstration of the colonies' ability to organize and act collectively in defense of their rights.

Legacy

The Continental Association is considered one of the first major steps toward the formation of the United States. In his first inaugural address in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln traced the origins of the Union to the Articles of Association, emphasizing the continuity between the Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, and the Articles of Confederation. The Association represented the colonies' collective resolve to resist British oppression and laid the foundation for the political unity that would eventually lead to the establishment of the United States.

The Continental Association's ban on British imports began on December 1, 1774, significantly reducing trade with Britain. In response, the British passed the New England Restraining Act, further escalating tensions. However, the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775 overshadowed the need for the boycott. Despite this, the agreement represented the colonies' growing unity and resolve to act collectively in defense of their rights. Abraham Lincoln later recognized the adoption of the Association as a foundational moment in the formation of the United States, noting it as the origin of the Union in his first inaugural address in 1861.

Background

The Coercive Acts, passed by Parliament in 1774, aimed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party and restructure colonial administration. This led to the convening of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774, where delegates from twelve colonies met to coordinate a response. Leaders such as George Washington, John Adams, and Patrick Henry were present. The Congress rejected a plan of reconciliation with Britain, fearing it would acknowledge Parliament's right to regulate colonial trade and impose taxes. Many Americans saw the Coercive Acts as a threat to their liberties, sparking the call for economic boycotts.

The boycott idea gained traction in May 1774, when the Boston Town Meeting, led by Samuel Adams, passed a resolution urging a halt to trade with Britain until the Boston Port Act, one of the Coercive Acts, was repealed. Paul Revere played a key role in spreading this message. Congress soon endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, which advocated for an embargo on British trade and called for the colonies to organize militias. This cooperation among the colonies laid the groundwork for the Continental Association, adopted on October 20, 1774, to address the growing crisis.

Provisions

The Continental Association immediately banned British tea and, starting December 1, 1774, all imports from Britain, Ireland, and the British West Indies. If the Intolerable Acts were not repealed by September 10, 1775, the colonies would also stop exporting goods to these regions. Article 2 specifically banned ships involved in the slave trade. The agreement also addressed the potential scarcity of goods, restricting merchants from price gouging. Local committees of inspection were established to monitor compliance, and violators were publicly ostracized. The Association promoted frugality, discouraging extravagance in clothing and even setting guidelines for simple funeral observances.

Enforcement

The Continental Association went into effect on December 1, 1774. Compliance was largely enforced through local committees, which were effective in most colonies except Georgia, where the need for British protection from Native Americans hindered participation. Public pressure played a significant role in enforcing the boycott, with newspapers and social networks shaming those who violated the agreement. In some cases, direct action was taken, such as in Annapolis, Maryland, where a merchant chose to burn his ship rather than face the consequences of importing British goods. In areas where enforcement was difficult, some counties enacted price ceilings to discourage smuggling.

Effects

The boycott caused a dramatic drop in trade with Britain, and by early 1775, the local committees of safety had become de facto revolutionary governments in many colonies. The Continental Association forced colonists to take sides, with Patriots supporting the boycott and Loyalists opposing it. In South Carolina, for example, Patriots dominated coastal areas, while Loyalists were more prevalent in the backcountry. The Association also led to the development of new governmental structures that supervised revolutionary activities.

Britain responded by passing the New England Restraining Act, which restricted the colonies' ability to trade with anyone except Britain and the British West Indies. This act, along with other punitive measures, only intensified the conflict, eventually leading to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. Although the boycott ended with the war, the Continental Association's lasting impact was its demonstration of the colonies' ability to organize and act collectively in defense of their rights.

Legacy

The Continental Association is considered one of the first major steps toward the formation of the United States. In his first inaugural address in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln traced the origins of the Union to the Articles of Association, emphasizing the continuity between the Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, and the Articles of Confederation. The Association represented the colonies' collective resolve to resist British oppression and laid the foundation for the political unity that would eventually lead to the establishment of the United States.

John Adams

October 30 [O.S. October 19] 1735 – July 4, 1826

Home:

Quincy, MA

Education:

Harvard University

Profession:

President, Vice President, Minister to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, Delegate to Continental Congress from Massachusetts

Info:

Adams was born in 1735 in Braintree, Massachusetts, and pursued a career in law after graduating from Harvard. His opposition to British policies, like the Stamp Act, propelled him into the revolutionary movement. Notably, he defended British soldiers in the Boston Massacre trials, showcasing his commitment to the rule of law. His career was marked by his advocacy for independence and effective leadership in the Continental Congress.

Following his significant contributions to the founding of the United States, Adams spent over a decade in Europe as a diplomat, playing a critical role in securing Dutch recognition and loans, as well as helping negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War. His later years were spent in politics and diplomacy, culminating in his presidency, where he navigated complex international tensions and internal party disputes. Adams retired to Quincy, Massachusetts, where he witnessed his son, John Quincy Adams, ascend to the presidency.

John Adams, often called the "Atlas of American Independence," played a pivotal role in initiating the American Revolution through his writings and political activities. He helped draft the Declaration of Independence and was a key figure in its passage through the Continental Congress. Adams's influence extended beyond the revolution, as he later served as the first Vice President and second President of the United States.

Following his significant contributions to the founding of the United States, Adams spent over a decade in Europe as a diplomat, playing a critical role in securing Dutch recognition and loans, as well as helping negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War. His later years were spent in politics and diplomacy, culminating in his presidency, where he navigated complex international tensions and internal party disputes. Adams retired to Quincy, Massachusetts, where he witnessed his son, John Quincy Adams, ascend to the presidency.

John Adams, often called the "Atlas of American Independence," played a pivotal role in initiating the American Revolution through his writings and political activities. He helped draft the Declaration of Independence and was a key figure in its passage through the Continental Congress. Adams's influence extended beyond the revolution, as he later served as the first Vice President and second President of the United States.

Samuel Adams

27 Sep 1722 – 2 Oct 1803

Home:

Boston, Massachusetts

Education:

Harvard University

Profession:

Governor of Massachusetts, Lt. Gov. of Mass., State Senator of Mass., Delegate to Continental Congress from Mass., Clerk of House of Representatives of Mass.

Info:

Samuel Adams, a key figure in the American Revolution, was born in Boston in 1722. Initially, he struggled in various jobs and faced financial difficulties but found his passion in politics, becoming a leader in Massachusetts's resistance against British control. His political activities and writings significantly shaped the early revolutionary movements.

Adams was instrumental in protesting against the Sugar and Stamp Acts and later the Townshend Acts, helping to organize resistance like the Boston Tea Party. His efforts contributed to the unity among the colonies against British policies, advocating for collective action through the creation of committees of correspondence and involvement in the Continental Congress.

Beyond his revolutionary contributions, Adams held various political roles in Massachusetts, serving as a state senator and governor. He remained influential in promoting republican values and governance until his death in 1803. Adams's legacy as a foundational American patriot is marked by his relentless advocacy for independence and democratic principles.

Adams was instrumental in protesting against the Sugar and Stamp Acts and later the Townshend Acts, helping to organize resistance like the Boston Tea Party. His efforts contributed to the unity among the colonies against British policies, advocating for collective action through the creation of committees of correspondence and involvement in the Continental Congress.

Beyond his revolutionary contributions, Adams held various political roles in Massachusetts, serving as a state senator and governor. He remained influential in promoting republican values and governance until his death in 1803. Adams's legacy as a foundational American patriot is marked by his relentless advocacy for independence and democratic principles.

John Alsop

1724 – 22 Nov 1794

Home:

New York, New York

Education:

Profession:

Politician, merchant

Info:

John Alsop Jr. (1724–1794) was an influential American merchant and politician who played a critical role in the early political life of New York City during the era of the American Revolution. Born in 1724 in New Windsor, in the Province of New York, he came from a family with deep colonial roots. His father, John Alsop Sr., was a lawyer primarily involved in real estate, and his mother, Abigail Sackett, was the daughter of Captain Joseph Sackett. On his father’s side, Alsop descended from Captain Richard Alsop and Hannah Underhill, part of a lineage that dated back to the earliest English settlers in the region. His ancestry also connected him to the Underhill and Feake families, including descendants of Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Alsop moved to New York City as a young man and, together with his younger brother Richard, entered the world of commerce. They established themselves as successful importers, specializing in cloth and dry goods. Over time, their business flourished, making the Alsop name synonymous with one of the great merchant houses of the city. This mercantile success afforded John Alsop the wealth and social standing that enabled him to become involved in civic affairs.

As his influence grew, Alsop was elected to represent New York County in the Province of New York Assembly. He also participated in important civic undertakings, helping to incorporate the New York Hospital Association and serving as its first governor from 1770 to 1784. By the mid-1770s, as tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain mounted, Alsop was drawn into the turbulent political sphere.

In 1774, when New York’s colonial assembly hesitated in responding to the Continental Congress, independent committees in each county chose delegates. Alsop was named a delegate to the First Continental Congress, serving alongside noted figures like John Jay and Philip Livingston. He signed the 1774 Continental Association, an agreement to boycott British goods—an act that demonstrated support for colonial rights despite personal business losses.

Though he was an active supporter of non-importation measures and a key figure in New York’s revolutionary Committees of Sixty, Alsop ultimately favored a peaceful resolution with Britain. As the Continental Congress moved toward declaring independence in 1776, he resigned his post rather than sign the Declaration of Independence. Nevertheless, he remained active in provisioning the Continental Army and supporting the cause in more moderate ways.

When British forces occupied New York, Alsop fled to Middletown, Connecticut, remaining there until the war’s conclusion. After the Revolution, he returned to help rebuild both his personal fortunes and the city’s commercial infrastructure. He served as president of the New York Chamber of Commerce, demonstrating his continued dedication to civic improvement.

In 1766, Alsop married Mary Frogat, with whom he had one daughter, Mary Alsop, who would later marry Rufus King, a Founding Father and U.S. Senator. John Alsop Jr. died on November 22, 1794, in Newtown, Queens County, leaving behind a legacy as a prominent merchant-patriot and an ancestor to several notable American figures. His remains are interred at Trinity Church Cemetery in Manhattan.

Alsop moved to New York City as a young man and, together with his younger brother Richard, entered the world of commerce. They established themselves as successful importers, specializing in cloth and dry goods. Over time, their business flourished, making the Alsop name synonymous with one of the great merchant houses of the city. This mercantile success afforded John Alsop the wealth and social standing that enabled him to become involved in civic affairs.

As his influence grew, Alsop was elected to represent New York County in the Province of New York Assembly. He also participated in important civic undertakings, helping to incorporate the New York Hospital Association and serving as its first governor from 1770 to 1784. By the mid-1770s, as tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain mounted, Alsop was drawn into the turbulent political sphere.

In 1774, when New York’s colonial assembly hesitated in responding to the Continental Congress, independent committees in each county chose delegates. Alsop was named a delegate to the First Continental Congress, serving alongside noted figures like John Jay and Philip Livingston. He signed the 1774 Continental Association, an agreement to boycott British goods—an act that demonstrated support for colonial rights despite personal business losses.

Though he was an active supporter of non-importation measures and a key figure in New York’s revolutionary Committees of Sixty, Alsop ultimately favored a peaceful resolution with Britain. As the Continental Congress moved toward declaring independence in 1776, he resigned his post rather than sign the Declaration of Independence. Nevertheless, he remained active in provisioning the Continental Army and supporting the cause in more moderate ways.

When British forces occupied New York, Alsop fled to Middletown, Connecticut, remaining there until the war’s conclusion. After the Revolution, he returned to help rebuild both his personal fortunes and the city’s commercial infrastructure. He served as president of the New York Chamber of Commerce, demonstrating his continued dedication to civic improvement.

In 1766, Alsop married Mary Frogat, with whom he had one daughter, Mary Alsop, who would later marry Rufus King, a Founding Father and U.S. Senator. John Alsop Jr. died on November 22, 1794, in Newtown, Queens County, leaving behind a legacy as a prominent merchant-patriot and an ancestor to several notable American figures. His remains are interred at Trinity Church Cemetery in Manhattan.

Edward Biddle

1738 – 5 September 1779

Home:

Philadelphia, PA

Education:

Profession:

Lawyer

Info:

Edward Biddle (1738–1779) was an American soldier, lawyer, and political leader from Pennsylvania who actively shaped the early revolutionary era. Born into a time of rising colonial discontent, Biddle became one of the voices advocating for American rights in the face of British policies. Although the details of his early life are sparse, his marriage in 1761 to Elizabeth Ross—sister of George Ross, another influential patriot—helped connect him to prominent families already embedded in the colonial political landscape. Through these ties, and under the mentorship of George Ross, Biddle studied law and, by 1767, he had gained admission to the Pennsylvania bar. Soon afterward, he and Elizabeth settled in Reading, where he established a law practice that would serve as the foundation for his public career.

While Biddle and his wife never had children, they came from extensive families, and their relatives would become well-known figures. Betsy Ross, famous for the legendary first American flag, was married to a nephew of his wife. In later generations, Biddle’s own family line produced distinguished public figures including his nephew, Congressman Richard Biddle, and financier Nicholas Biddle, a central figure in early American banking.

Biddle’s entry into public life came in 1767, when he won election to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly as a representative for Berks County. He served in this legislative body until its dissolution at the start of the Revolution. His capabilities and interests went beyond local governance: that same year, he joined the American Philosophical Society, reflecting a broader engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. As the political climate heated up, Biddle became more deeply involved in the radical Whig faction within Pennsylvania’s political scene. He was instrumental in shaping the colony’s response to British actions and guiding it toward a path of resistance and independence.

By 1774, the colony’s legislature was divided, especially regarding how to respond to escalating tensions with Great Britain. That year, Pennsylvania chose a delegation to the First Continental Congress consisting of both moderates and radicals. Biddle joined Thomas Mifflin, John Morton, and his brother-in-law George Ross among the more radical delegates. During the Congress, Biddle played a key role on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Rights and oversaw the printing of the Congress’s resolutions. The Continental Association, advocating non-importation of British goods, was renewed under his watchful eye.

Pennsylvania’s internal conflicts continued into 1775 when Governor John Penn sought to chart a conciliatory course with Britain. Biddle, however, stood firmly with the Whigs who, along with figures like John Dickinson, steered the Assembly toward supporting the actions of the Continental Congress instead of pursuing appeasement. His leadership was recognized when he was elected Speaker of the Assembly, replacing the moderate Joseph Galloway.

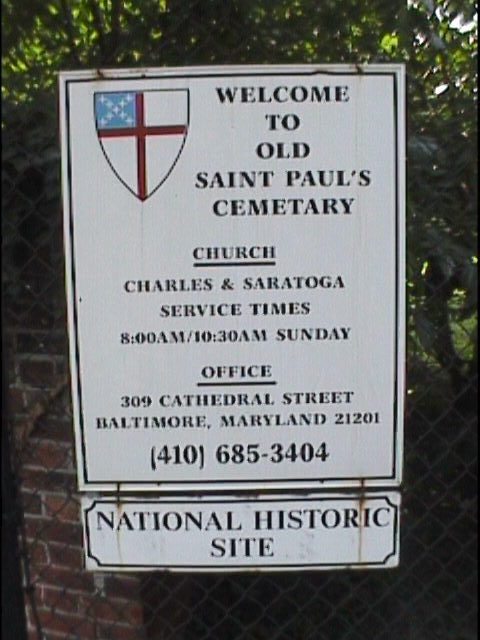

Over the course of the Revolution, Biddle’s health declined, and he eventually traveled to Maryland, where he died in Chatsworth, Baltimore County, on September 5, 1779. He was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard in Baltimore. Although his life was relatively brief, Edward Biddle’s legal, political, and legislative work contributed significantly to Pennsylvania’s—and the nation’s—progress toward independence.

While Biddle and his wife never had children, they came from extensive families, and their relatives would become well-known figures. Betsy Ross, famous for the legendary first American flag, was married to a nephew of his wife. In later generations, Biddle’s own family line produced distinguished public figures including his nephew, Congressman Richard Biddle, and financier Nicholas Biddle, a central figure in early American banking.

Biddle’s entry into public life came in 1767, when he won election to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly as a representative for Berks County. He served in this legislative body until its dissolution at the start of the Revolution. His capabilities and interests went beyond local governance: that same year, he joined the American Philosophical Society, reflecting a broader engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. As the political climate heated up, Biddle became more deeply involved in the radical Whig faction within Pennsylvania’s political scene. He was instrumental in shaping the colony’s response to British actions and guiding it toward a path of resistance and independence.

By 1774, the colony’s legislature was divided, especially regarding how to respond to escalating tensions with Great Britain. That year, Pennsylvania chose a delegation to the First Continental Congress consisting of both moderates and radicals. Biddle joined Thomas Mifflin, John Morton, and his brother-in-law George Ross among the more radical delegates. During the Congress, Biddle played a key role on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Rights and oversaw the printing of the Congress’s resolutions. The Continental Association, advocating non-importation of British goods, was renewed under his watchful eye.

Pennsylvania’s internal conflicts continued into 1775 when Governor John Penn sought to chart a conciliatory course with Britain. Biddle, however, stood firmly with the Whigs who, along with figures like John Dickinson, steered the Assembly toward supporting the actions of the Continental Congress instead of pursuing appeasement. His leadership was recognized when he was elected Speaker of the Assembly, replacing the moderate Joseph Galloway.

Over the course of the Revolution, Biddle’s health declined, and he eventually traveled to Maryland, where he died in Chatsworth, Baltimore County, on September 5, 1779. He was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard in Baltimore. Although his life was relatively brief, Edward Biddle’s legal, political, and legislative work contributed significantly to Pennsylvania’s—and the nation’s—progress toward independence.

No Image

Richard Bland

6 May 1710 – 26 Oct 1776

Home:

Jordan's Point, VA

Education:

College of William & Mary and Edinburgh University

Profession:

Planter, Lawyer and Politician

Info:

Richard Bland (1710–1776) was a prominent American Founding Father, planter, lawyer, and politician from Virginia. Born on May 6, 1710, he likely entered the world either at his family’s main plantation at Jordan’s Point along the James River or at their residence in Williamsburg. Both parents hailed from the First Families of Virginia, ensuring Bland grew up within a powerful network of influential colonists. When he was just shy of ten, both parents died, leaving Bland and his siblings under the guardianship of uncles William and Richard Randolph. This early environment shaped Bland’s future as a thoughtful scholar and public servant.

Bland received a solid education for his time. After his formative years of home study and guardianship, he attended the College of William & Mary, one of the premier institutions in the colony. Seeking further intellectual stimulation, he continued his studies in Scotland at Edinburgh University. He was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1746 but never practiced law publicly. Instead, he used his legal knowledge as a firm grounding for his work in political life and scholarly writing.

Upon reaching adulthood, Bland inherited his father’s Jordan Point plantation and other parcels of land, managing them with enslaved labor. Although later recognized as an early critic of slavery’s principles, he remained part of the system that sustained Virginia’s plantation economy.

Bland’s true mark on history lies in his lengthy political career and intellectual contributions. Elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1742, he served continuously for over three decades until the American Revolution disrupted the colonial government. During this period, he became a prominent figure, often working quietly behind the scenes. He excelled in committee work, particularly in drafting legislation and negotiating laws, and earned a reputation as one of the most influential figures in the assembly’s last quarter century. His close cousins, Peyton Randolph and Jane Randolph Jefferson (mother of Thomas Jefferson), helped create a network of family alliances that influenced Virginia’s political landscape. Bland’s mentorship of his younger cousin Thomas Jefferson would bear fruit as Jefferson rose to national prominence.

Bland’s written works played a significant role in shaping colonial thought. During the Parson’s Cause controversy (1759–1760), he penned a pamphlet opposing higher clerical pay and the appointment of a bishop. In 1766, he published his most influential piece, An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies, where he argued against Parliament’s authority to tax colonists without their consent. His reasoning contributed to the emerging ethos of “no taxation without representation” and earned praise from Jefferson for its clear-sighted analysis.

In the turbulent 1770s, Bland represented Virginia in the First Continental Congress, signing the Continental Association in 1774. Although he declined to serve in the Second Continental Congress after August 1775 due to age and health, he continued to shape Virginia’s future. He helped draft Virginia’s first state constitution in mid-1776 and was named to the new House of Delegates that October.

Bland collapsed and died in Williamsburg on October 26, 1776. He was buried at Jordan’s Point. His lasting legacy includes a rich intellectual heritage, a formative influence on Jefferson, and the honor of having Virginia’s Bland County and Richard Bland College bear his name.

Bland received a solid education for his time. After his formative years of home study and guardianship, he attended the College of William & Mary, one of the premier institutions in the colony. Seeking further intellectual stimulation, he continued his studies in Scotland at Edinburgh University. He was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1746 but never practiced law publicly. Instead, he used his legal knowledge as a firm grounding for his work in political life and scholarly writing.

Upon reaching adulthood, Bland inherited his father’s Jordan Point plantation and other parcels of land, managing them with enslaved labor. Although later recognized as an early critic of slavery’s principles, he remained part of the system that sustained Virginia’s plantation economy.

Bland’s true mark on history lies in his lengthy political career and intellectual contributions. Elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1742, he served continuously for over three decades until the American Revolution disrupted the colonial government. During this period, he became a prominent figure, often working quietly behind the scenes. He excelled in committee work, particularly in drafting legislation and negotiating laws, and earned a reputation as one of the most influential figures in the assembly’s last quarter century. His close cousins, Peyton Randolph and Jane Randolph Jefferson (mother of Thomas Jefferson), helped create a network of family alliances that influenced Virginia’s political landscape. Bland’s mentorship of his younger cousin Thomas Jefferson would bear fruit as Jefferson rose to national prominence.

Bland’s written works played a significant role in shaping colonial thought. During the Parson’s Cause controversy (1759–1760), he penned a pamphlet opposing higher clerical pay and the appointment of a bishop. In 1766, he published his most influential piece, An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies, where he argued against Parliament’s authority to tax colonists without their consent. His reasoning contributed to the emerging ethos of “no taxation without representation” and earned praise from Jefferson for its clear-sighted analysis.

In the turbulent 1770s, Bland represented Virginia in the First Continental Congress, signing the Continental Association in 1774. Although he declined to serve in the Second Continental Congress after August 1775 due to age and health, he continued to shape Virginia’s future. He helped draft Virginia’s first state constitution in mid-1776 and was named to the new House of Delegates that October.

Bland collapsed and died in Williamsburg on October 26, 1776. He was buried at Jordan’s Point. His lasting legacy includes a rich intellectual heritage, a formative influence on Jefferson, and the honor of having Virginia’s Bland County and Richard Bland College bear his name.

Simon Boerum

29 Feb 1724 – 11 July 1775

Home:

Brooklyn, New York

Education:

Dutch school in Flatbush

Profession:

Farmer, Miller and Politician

Info:

Simon Boerum (1724–1775) was an influential colonial-era farmer, miller, and political leader from Long Island, New York, during a period marked by growing tensions with Great Britain. Born on February 29, 1724, he came from a family of Dutch ancestry who had settled in the region when it was still part of New Netherland. His parents, William Jacob Boerum and Rachel Bloom Boerum, farmed in the town of New Lots in Kings County (an area that would later become part of Brooklyn). Baptized into the Dutch Reformed Church on March 8, young Boerum benefited from the Dutch cultural and religious traditions of the community. He received his early education at a local Dutch school in Flatbush, preparing him for both the practical demands of farm life and the evolving world of colonial politics.

As a young man, Boerum embraced a life closely tied to the land. He farmed and operated a mill in Flatbush, taking advantage of the fertile soil and the area’s need for local milling services. In 1748, he purchased a home and garden at the intersection of what are now Fulton and Hoyt Streets in downtown Brooklyn. That same year, on April 30, he married Maria Schenck, with whom he shared this home for the remainder of their lives. Their marriage reflected the interwoven families and networks that characterized the Dutch communities of Long Island and played a role in Boerum’s local prominence.

Boerum’s public career began in 1750, when Governor George Clinton appointed him as county clerk for Kings County. He would hold this position for the rest of his life, evidence of the trust and stability he represented in local governance. His capabilities and steady leadership led to a seat in the Province of New York Assembly after 1761. As political tensions between Great Britain and the American colonies intensified over taxation, representation, and governance, Boerum found himself at the center of increasingly complex political debates.

In 1774, when the New York Assembly failed to reach consensus on sending delegates to the newly proposed Continental Congress, Kings County selected Boerum to represent their interests. On October 1, 1774, the Continental Congress formally added him to New York’s delegation. Once in Philadelphia, Boerum proved sympathetic to more radical measures. He supported the Continental Association, a non-importation agreement aimed at pressuring Britain through economic means. Boerum also assisted in defeating the Galloway Plan, a more moderate proposal that sought reconciliation with England rather than moving toward independence.

The tumult of the revolutionary period continued into 1775. The New York Assembly, hostile to the resolutions of the First Continental Congress, was abruptly adjourned. In response, Boerum was elected to the revolutionary New York Provincial Congress, representing a shift away from traditional colonial governance toward a revolutionary structure. That body re-appointed him to the Continental Congress, signifying his importance and reliability as a leader. However, failing health intervened, and Boerum returned home from Philadelphia.

He died at his Brooklyn residence on July 11, 1775, his life cut short as the crisis that would lead to the American Revolution intensified. Initially buried in the Dutch Burying Ground in New Lots, Boerum and his wife were later reinterred in Green-Wood Cemetery in 1848, ensuring his memory endures in the place he called home.

As a young man, Boerum embraced a life closely tied to the land. He farmed and operated a mill in Flatbush, taking advantage of the fertile soil and the area’s need for local milling services. In 1748, he purchased a home and garden at the intersection of what are now Fulton and Hoyt Streets in downtown Brooklyn. That same year, on April 30, he married Maria Schenck, with whom he shared this home for the remainder of their lives. Their marriage reflected the interwoven families and networks that characterized the Dutch communities of Long Island and played a role in Boerum’s local prominence.

Boerum’s public career began in 1750, when Governor George Clinton appointed him as county clerk for Kings County. He would hold this position for the rest of his life, evidence of the trust and stability he represented in local governance. His capabilities and steady leadership led to a seat in the Province of New York Assembly after 1761. As political tensions between Great Britain and the American colonies intensified over taxation, representation, and governance, Boerum found himself at the center of increasingly complex political debates.

In 1774, when the New York Assembly failed to reach consensus on sending delegates to the newly proposed Continental Congress, Kings County selected Boerum to represent their interests. On October 1, 1774, the Continental Congress formally added him to New York’s delegation. Once in Philadelphia, Boerum proved sympathetic to more radical measures. He supported the Continental Association, a non-importation agreement aimed at pressuring Britain through economic means. Boerum also assisted in defeating the Galloway Plan, a more moderate proposal that sought reconciliation with England rather than moving toward independence.

The tumult of the revolutionary period continued into 1775. The New York Assembly, hostile to the resolutions of the First Continental Congress, was abruptly adjourned. In response, Boerum was elected to the revolutionary New York Provincial Congress, representing a shift away from traditional colonial governance toward a revolutionary structure. That body re-appointed him to the Continental Congress, signifying his importance and reliability as a leader. However, failing health intervened, and Boerum returned home from Philadelphia.

He died at his Brooklyn residence on July 11, 1775, his life cut short as the crisis that would lead to the American Revolution intensified. Initially buried in the Dutch Burying Ground in New Lots, Boerum and his wife were later reinterred in Green-Wood Cemetery in 1848, ensuring his memory endures in the place he called home.

No Image

Richard Caswell

3 Aug 1729 – 10 Nov 1789

Home:

Kinston, NC

Education:

Profession:

Governor, Statesman, Lawyer, and Military Leader

Info:

Richard Caswell (1729–1789) was a prominent American statesman, lawyer, and military leader who played a crucial role in shaping North Carolina’s early governance and its participation in the Revolutionary War. Born on August 3, 1729, in what is now Baltimore County, Maryland, Caswell’s family relocated to New Bern, North Carolina, during his youth. He benefited from an upbringing that emphasized public service, and by 1750, he was deputy surveyor for the province. Caswell grew into a man of diverse talents and enterprises, working as a lawyer, farmer, land speculator, tanner, and holding leadership roles in the Freemasons.

A dedicated public servant, Caswell spent 17 years as a member of the North Carolina House of Burgesses. While in office, he introduced the bill that led to the establishment of “Kingston,” later renamed Kinston during the Revolution. Caswell’s leadership on the home front intersected with military affairs during the Regulator Movement, notably at the Battle of Alamance in 1771, where he commanded the right wing of Governor William Tryon’s forces.

In the emerging struggle with Britain, Caswell was an influential figure. As a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774, he signed the Continental Association, marking him as a supporter of colonial rights. He served again in 1775 before dedicating himself more fully to military roles in the Southern theater of the Revolution. Appointed to command the New Bern minutemen in 1776, he led the Patriot forces to victory at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, a turning point in securing North Carolina for the American cause. Though later faced with defeat at Camden in 1780—owing largely to the collapse of neighboring militia—Caswell’s overall service bolstered the state’s revolutionary effort. Commissioned successively as colonel, brigadier general, and major general of militia, he remained involved in military leadership until the war’s conclusion.

Caswell’s political achievements are equally significant. He presided over the North Carolina Provincial Congress that drafted the state’s first constitution in 1776. Named acting governor as the Congress adjourned, he then became the state’s first governor under the new constitution, serving from 1777 to 1780. Prevented by law from serving more than three consecutive one-year terms, he returned to public life afterward as comptroller and as a state senator. In 1785, he was elected governor again, serving until 1787. Though chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Caswell did not attend. At his death in 1789, he was serving as Speaker of the North Carolina Senate, illustrating a lifelong commitment to guiding the state’s public policy.

Caswell’s family life was marked by two marriages—first to Mary Mackilwean, then to Sarah Heritage—resulting in multiple children, several of whom served in the military. His sons William and Richard both fought in the Revolution, continuing their father’s legacy of service. Caswell died on November 10, 1789, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and was likely buried near his Kinston home, where a memorial now stands. Caswell County, Fort Caswell, and educational provisions in the state’s early constitution all reflect his enduring influence.

A dedicated public servant, Caswell spent 17 years as a member of the North Carolina House of Burgesses. While in office, he introduced the bill that led to the establishment of “Kingston,” later renamed Kinston during the Revolution. Caswell’s leadership on the home front intersected with military affairs during the Regulator Movement, notably at the Battle of Alamance in 1771, where he commanded the right wing of Governor William Tryon’s forces.

In the emerging struggle with Britain, Caswell was an influential figure. As a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774, he signed the Continental Association, marking him as a supporter of colonial rights. He served again in 1775 before dedicating himself more fully to military roles in the Southern theater of the Revolution. Appointed to command the New Bern minutemen in 1776, he led the Patriot forces to victory at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, a turning point in securing North Carolina for the American cause. Though later faced with defeat at Camden in 1780—owing largely to the collapse of neighboring militia—Caswell’s overall service bolstered the state’s revolutionary effort. Commissioned successively as colonel, brigadier general, and major general of militia, he remained involved in military leadership until the war’s conclusion.

Caswell’s political achievements are equally significant. He presided over the North Carolina Provincial Congress that drafted the state’s first constitution in 1776. Named acting governor as the Congress adjourned, he then became the state’s first governor under the new constitution, serving from 1777 to 1780. Prevented by law from serving more than three consecutive one-year terms, he returned to public life afterward as comptroller and as a state senator. In 1785, he was elected governor again, serving until 1787. Though chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Caswell did not attend. At his death in 1789, he was serving as Speaker of the North Carolina Senate, illustrating a lifelong commitment to guiding the state’s public policy.

Caswell’s family life was marked by two marriages—first to Mary Mackilwean, then to Sarah Heritage—resulting in multiple children, several of whom served in the military. His sons William and Richard both fought in the Revolution, continuing their father’s legacy of service. Caswell died on November 10, 1789, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and was likely buried near his Kinston home, where a memorial now stands. Caswell County, Fort Caswell, and educational provisions in the state’s early constitution all reflect his enduring influence.

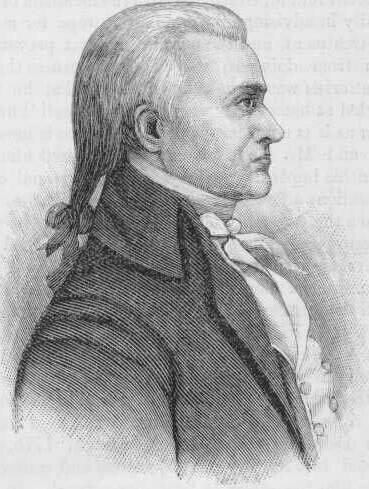

Samuel Chase

17 Apr 1741 – 19 Jun 1811

Home:

Baltimore, MD

Education:

Studied Law

Profession:

Associate Justice, Judge

Info:

Samuel Chase (1741–1811) was an American Founding Father, distinguished jurist, and leading figure in the country’s early political and legal affairs. Born on April 17, 1741, near Princess Anne, Maryland, he was the son of Reverend Thomas Chase, an Anglican clergyman who had immigrated from England. Educated primarily at home, Chase studied law under John Hall in Annapolis, Maryland, and by 1761 had launched a thriving legal practice in that city. Known for his passionate and at times combative personality—earning him the nickname “Old Bacon Face”—Chase quickly positioned himself as a formidable attorney and political operator.

By 1764, Chase had entered the Maryland General Assembly, a body in which he served for two decades. An early advocate for colonial rights, he forcefully opposed British taxation and joined with fellow patriots such as William Paca to found a local Sons of Liberty chapter. His growing political influence gained him a seat in the Continental Congress, where he represented Maryland, signed the Continental Association in 1774, and later affixed his name to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. These acts placed him firmly in the pantheon of Founding Fathers.

As the new nation took shape, Chase’s legal acumen and strong personality made him a key figure in both state and federal government. He was a fervent Anti-Federalist during the debates over the U.S. Constitution’s ratification in Maryland, though the state eventually voted to approve the document. After serving as chief justice on the District Criminal Court in Baltimore and the Maryland General Court, Chase’s stature caught the attention of President George Washington. In 1796, Washington appointed him as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He took his seat in 1796 and would serve until his death, helping shape the young nation’s jurisprudence at a time when the contours of federal authority were still untested.

Chase’s judicial career, however, became fraught with controversy. A staunch Federalist, he was outspoken against what he saw as the excesses of the Jeffersonian Republicans. His partisan commentary on the bench—particularly critical remarks about legislation favored by the Jefferson administration—triggered a dramatic political clash. In 1804, the House of Representatives impeached him on charges that he allowed his political biases to influence his judicial decisions. This was the first and only impeachment of a U.S. Supreme Court justice to date. Tried before the Senate in 1805, Chase was acquitted, thus setting a crucial precedent for judicial independence. His acquittal affirmed that judges could not be removed simply for their political beliefs or judicial philosophy—an important reinforcement of the separation of powers and the integrity of the judiciary.

Despite this tumultuous chapter, Chase remained on the Supreme Court until his death on June 19, 1811. He was buried in Baltimore’s Old Saint Paul’s Cemetery. While his legacy is complicated by his ownership of enslaved people and his often fiery temperament, Samuel Chase’s contributions to the Revolution, his role in shaping legal precedent, and his defense of judicial independence mark him as a significant figure in early American history.

By 1764, Chase had entered the Maryland General Assembly, a body in which he served for two decades. An early advocate for colonial rights, he forcefully opposed British taxation and joined with fellow patriots such as William Paca to found a local Sons of Liberty chapter. His growing political influence gained him a seat in the Continental Congress, where he represented Maryland, signed the Continental Association in 1774, and later affixed his name to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. These acts placed him firmly in the pantheon of Founding Fathers.

As the new nation took shape, Chase’s legal acumen and strong personality made him a key figure in both state and federal government. He was a fervent Anti-Federalist during the debates over the U.S. Constitution’s ratification in Maryland, though the state eventually voted to approve the document. After serving as chief justice on the District Criminal Court in Baltimore and the Maryland General Court, Chase’s stature caught the attention of President George Washington. In 1796, Washington appointed him as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He took his seat in 1796 and would serve until his death, helping shape the young nation’s jurisprudence at a time when the contours of federal authority were still untested.

Chase’s judicial career, however, became fraught with controversy. A staunch Federalist, he was outspoken against what he saw as the excesses of the Jeffersonian Republicans. His partisan commentary on the bench—particularly critical remarks about legislation favored by the Jefferson administration—triggered a dramatic political clash. In 1804, the House of Representatives impeached him on charges that he allowed his political biases to influence his judicial decisions. This was the first and only impeachment of a U.S. Supreme Court justice to date. Tried before the Senate in 1805, Chase was acquitted, thus setting a crucial precedent for judicial independence. His acquittal affirmed that judges could not be removed simply for their political beliefs or judicial philosophy—an important reinforcement of the separation of powers and the integrity of the judiciary.

Despite this tumultuous chapter, Chase remained on the Supreme Court until his death on June 19, 1811. He was buried in Baltimore’s Old Saint Paul’s Cemetery. While his legacy is complicated by his ownership of enslaved people and his often fiery temperament, Samuel Chase’s contributions to the Revolution, his role in shaping legal precedent, and his defense of judicial independence mark him as a significant figure in early American history.

Stephen Crane

1709 – 1 July 1780

Home:

Elizabeth, NJ

Education:

Profession:

Colonial Politician and Civic Leader

Info:

Stephen Crane (1709 – July 1, 1780) was a prominent American colonial politician and civic leader from Elizabethtown, in what is now Elizabeth, New Jersey. Born into a respected family during the early 18th century, Crane’s life spanned the turbulent years leading up to and during the American Revolution. Over the course of his career, he would serve in various significant roles, from local sheriff to member of the Continental Congress, helping to shape the political landscape in both his home colony and the emerging nation.

From an early stage, Crane was involved in public affairs. He began as sheriff of Essex County and soon became active in the local town committee. His reputation for fairness and capability led to his appointment as a judge of the court of common pleas. By the 1760s, Crane’s steady rise in colonial government was evident: between 1766 and 1773, he served in the colony’s General Assembly, even becoming its speaker in 1771. His influence did not stop there; he also held the office of mayor of Elizabethtown. Such positions reflected not only his leadership qualities but also the trust placed in him by his community and peers.

As tensions escalated between the American colonies and Great Britain, Crane emerged as a committed advocate for colonial rights. He deeply opposed the increasing taxes and restrictions imposed by the British Parliament, a stance that led to direct involvement in the larger political struggle. Alongside Matthias Hatfield, Crane is recorded as having traveled to England, where he did not hesitate to voice his protest against unjust taxation. This experience underscored Crane’s growing role in the movement toward independence.

From 1774 to 1776, Stephen Crane represented New Jersey in the Continental Congress, placing him among the foremost leaders of the era. Alongside other delegates, he signed the Continental Association, a pivotal agreement that established a unified boycott of British goods. Although he did not return for subsequent sessions due to urgent political divisions within New Jersey—specifically the longstanding regional tensions between East and West Jersey—Crane’s early contributions to the Continental Congress helped set the stage for future American unity and governance.

Throughout the Revolutionary War period, Crane remained active in New Jersey politics, holding various public offices and participating in the state’s Provincial Congress, General Assembly, and Legislative Council. His roles were critical in guiding New Jersey through the complexities of the conflict.

Tragically, Crane’s life ended violently and prematurely. During the British invasion of northern New Jersey in 1780, Hessian soldiers passed through Elizabethtown on their way to the Battle of Springfield. Crane, caught in their path, was bayoneted. He succumbed to his wounds on July 1, 1780, and was laid to rest in the First Presbyterian Church cemetery in Elizabeth, alongside his wife and father.

Stephen Crane’s legacy extended through his descendants, many of whom served in the nation’s military and civic affairs. Notably, his lineage included Jonathan Townley Crane and the celebrated American author Stephen Crane, who achieved fame for his novel The Red Badge of Courage. In this way, Stephen Crane’s impact resonated far beyond his own lifetime, weaving his name into the broader tapestry of American history and culture.

From an early stage, Crane was involved in public affairs. He began as sheriff of Essex County and soon became active in the local town committee. His reputation for fairness and capability led to his appointment as a judge of the court of common pleas. By the 1760s, Crane’s steady rise in colonial government was evident: between 1766 and 1773, he served in the colony’s General Assembly, even becoming its speaker in 1771. His influence did not stop there; he also held the office of mayor of Elizabethtown. Such positions reflected not only his leadership qualities but also the trust placed in him by his community and peers.

As tensions escalated between the American colonies and Great Britain, Crane emerged as a committed advocate for colonial rights. He deeply opposed the increasing taxes and restrictions imposed by the British Parliament, a stance that led to direct involvement in the larger political struggle. Alongside Matthias Hatfield, Crane is recorded as having traveled to England, where he did not hesitate to voice his protest against unjust taxation. This experience underscored Crane’s growing role in the movement toward independence.

From 1774 to 1776, Stephen Crane represented New Jersey in the Continental Congress, placing him among the foremost leaders of the era. Alongside other delegates, he signed the Continental Association, a pivotal agreement that established a unified boycott of British goods. Although he did not return for subsequent sessions due to urgent political divisions within New Jersey—specifically the longstanding regional tensions between East and West Jersey—Crane’s early contributions to the Continental Congress helped set the stage for future American unity and governance.

Throughout the Revolutionary War period, Crane remained active in New Jersey politics, holding various public offices and participating in the state’s Provincial Congress, General Assembly, and Legislative Council. His roles were critical in guiding New Jersey through the complexities of the conflict.

Tragically, Crane’s life ended violently and prematurely. During the British invasion of northern New Jersey in 1780, Hessian soldiers passed through Elizabethtown on their way to the Battle of Springfield. Crane, caught in their path, was bayoneted. He succumbed to his wounds on July 1, 1780, and was laid to rest in the First Presbyterian Church cemetery in Elizabeth, alongside his wife and father.

Stephen Crane’s legacy extended through his descendants, many of whom served in the nation’s military and civic affairs. Notably, his lineage included Jonathan Townley Crane and the celebrated American author Stephen Crane, who achieved fame for his novel The Red Badge of Courage. In this way, Stephen Crane’s impact resonated far beyond his own lifetime, weaving his name into the broader tapestry of American history and culture.

Thomas Cushing III

24 Mar 1725 – 28 Feb 1788

Home:

Boston, MA

Education:

Harvard

Profession:

Political Figure, Merchant, and Lawyer

Info:

Thomas Cushing III (1725–1788) was a prominent Massachusetts political figure, merchant, and lawyer who played a significant role in the tumultuous years leading up to American independence and the early formation of the state’s government. Born on March 24, 1725, into a well-established Boston family, Cushing enjoyed the advantages of wealth and education. He graduated from Harvard in 1744, studied law, and joined his family’s prosperous merchant business. His marriage to Deborah Fletcher in 1747 produced five children, cementing family ties that would bolster his local prominence.

Cushing’s political career began at the local level when he won election as a Boston selectman in 1753, a position he held until 1763. He advanced to the colonial assembly (General Court) in 1761, where he quickly emerged as a steady, moderate voice. In 1766, after the governor rejected the assembly’s preferred candidate, James Otis, Cushing was chosen as a compromise speaker of the house. He would serve in that office until the British governor dissolved the assembly in 1774. As speaker, his signature appeared on numerous petitions and protests against British policies, leading authorities in London to view him as a radical troublemaker.

Although not as fiery as some of his colleagues—he tended toward moderation—Cushing was closely associated with key Patriot leaders. He formed a productive political alliance with John Hancock, contributing financially and often working behind the scenes, which enabled Hancock to remain the more visible leader. Cushing’s correspondence with Benjamin Franklin, who represented the assembly’s interests in London, highlighted his preference for calm negotiation and attempts at reconciliation, even as tensions escalated.

Cushing represented Massachusetts in the First and Second Continental Congresses (1774–1775). He signed the Continental Association, which organized a boycott of British goods. However, his reluctance to fully embrace independence cost him politically. In late 1775, as sentiment for breaking with Britain intensified, he lost his seat in Congress to Elbridge Gerry, a vocal supporter of independence.

Despite this setback, Cushing remained active in Massachusetts politics. During the Revolutionary War, he served as a commissary, provisioning both American and allied French troops—a role he and other merchants used to advance their business interests. He was also involved in attempts to stabilize the faltering wartime economy, joining other leaders in efforts to control runaway inflation, albeit without much success.

With the establishment of Massachusetts’ state government in 1780, Cushing continued his public service. He briefly served as the state senate’s first president before being elected as Massachusetts’ first lieutenant governor that same year. He served under his old ally John Hancock for several terms. When Hancock resigned in 1785, Cushing served briefly as acting governor until James Bowdoin assumed the office. Although he was frequently depicted by opponents as overshadowed by Hancock, Cushing’s steady presence and managerial capabilities were vital to the state’s early governance.

Thomas Cushing died in office on February 28, 1788, and was buried in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground. His legacy endures in the town of Cushing, Maine, which bears his name, and in the memory of his moderate, pragmatic approach to the challenges of the Revolutionary era.

Cushing’s political career began at the local level when he won election as a Boston selectman in 1753, a position he held until 1763. He advanced to the colonial assembly (General Court) in 1761, where he quickly emerged as a steady, moderate voice. In 1766, after the governor rejected the assembly’s preferred candidate, James Otis, Cushing was chosen as a compromise speaker of the house. He would serve in that office until the British governor dissolved the assembly in 1774. As speaker, his signature appeared on numerous petitions and protests against British policies, leading authorities in London to view him as a radical troublemaker.

Although not as fiery as some of his colleagues—he tended toward moderation—Cushing was closely associated with key Patriot leaders. He formed a productive political alliance with John Hancock, contributing financially and often working behind the scenes, which enabled Hancock to remain the more visible leader. Cushing’s correspondence with Benjamin Franklin, who represented the assembly’s interests in London, highlighted his preference for calm negotiation and attempts at reconciliation, even as tensions escalated.

Cushing represented Massachusetts in the First and Second Continental Congresses (1774–1775). He signed the Continental Association, which organized a boycott of British goods. However, his reluctance to fully embrace independence cost him politically. In late 1775, as sentiment for breaking with Britain intensified, he lost his seat in Congress to Elbridge Gerry, a vocal supporter of independence.

Despite this setback, Cushing remained active in Massachusetts politics. During the Revolutionary War, he served as a commissary, provisioning both American and allied French troops—a role he and other merchants used to advance their business interests. He was also involved in attempts to stabilize the faltering wartime economy, joining other leaders in efforts to control runaway inflation, albeit without much success.

With the establishment of Massachusetts’ state government in 1780, Cushing continued his public service. He briefly served as the state senate’s first president before being elected as Massachusetts’ first lieutenant governor that same year. He served under his old ally John Hancock for several terms. When Hancock resigned in 1785, Cushing served briefly as acting governor until James Bowdoin assumed the office. Although he was frequently depicted by opponents as overshadowed by Hancock, Cushing’s steady presence and managerial capabilities were vital to the state’s early governance.

Thomas Cushing died in office on February 28, 1788, and was buried in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground. His legacy endures in the town of Cushing, Maine, which bears his name, and in the memory of his moderate, pragmatic approach to the challenges of the Revolutionary era.

John De Hart

25 July 1727 – 1 June 1795

Home:

Education:

Profession:

Info:

John De Hart was born on July 25, 1727, in Elizabethtown, now Elizabeth, New Jersey, to Jacob and Abigail (Crane) De Hart. He pursued a career in law and was admitted to the bar in 1770. De Hart married Sarah Dagworthy, with whom he had eight children: John, Jacob, Matthias, Stephen, Sarah, Abigail, Jane, and Louisa. His prominence rose rapidly, and in 1774, he represented New Jersey at the First Continental Congress, where he supported the non-importation agreements aimed at pressuring Britain, yet favored reconciliation. He continued as a delegate in the Second Continental Congress in 1775 but resigned on November 13 due to growing disagreements over independence from Great Britain. The resignation was accepted by the New Jersey General Assembly on November 22.

In 1776, De Hart actively contributed to establishing an independent government in New Jersey. He participated in the state convention and served on the committee that drafted the New Jersey State Constitution in June of that year. On September 4, 1776, he was appointed to the New Jersey Supreme Court, but was later replaced by Governor William Livingston in February 1777 due to his failure to attend court sessions regularly. Despite this setback, De Hart continued to practice law successfully. His final public role was serving as Mayor of Elizabeth, elected in November 1789, a position he held until his death. John De Hart passed away at his Elizabeth home on June 1, 1795, and was buried in St. John's Episcopal Churchyard. His legacy includes the historic De Hart House and familial ties to General Winfield Scott through his granddaughter Maria D. Mayo.

In 1776, De Hart actively contributed to establishing an independent government in New Jersey. He participated in the state convention and served on the committee that drafted the New Jersey State Constitution in June of that year. On September 4, 1776, he was appointed to the New Jersey Supreme Court, but was later replaced by Governor William Livingston in February 1777 due to his failure to attend court sessions regularly. Despite this setback, De Hart continued to practice law successfully. His final public role was serving as Mayor of Elizabeth, elected in November 1789, a position he held until his death. John De Hart passed away at his Elizabeth home on June 1, 1795, and was buried in St. John's Episcopal Churchyard. His legacy includes the historic De Hart House and familial ties to General Winfield Scott through his granddaughter Maria D. Mayo.

Silas Deane

4 Jan 1738 – 23 Sept 1789

Home:

Education:

Profession:

Info:

Silas Deane was born on January 4, 1738, in Groton, Connecticut. Educated at Yale, where he graduated in 1758, Deane briefly practiced law before moving to Wethersfield, Connecticut, to build a successful career as a merchant. He married twice, first to Mehitable (Nott) Webb in 1763, with whom he had one son, Jesse. After Mehitable’s death in 1767, Deane married Elizabeth (Saltonstall) Evards in 1770. Elizabeth passed away in 1777 while Deane was abroad. Politically active, he served in the Connecticut House of Representatives beginning in 1768 and was appointed to the Wethersfield Committee of Correspondence in 1769. From 1774 to 1776, he served as a Connecticut delegate to the Continental Congress, signing the Continental Association and aiding in establishing the U.S. Navy.

In March 1776, Deane was appointed as the first American envoy to France, tasked with obtaining crucial financial and military support. He successfully negotiated the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France alongside Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee. Deane recruited notable foreign officers such as Lafayette, von Steuben, and Pulaski, significantly bolstering the American military effort. However, controversy arose over his financial dealings, exacerbated by rival Arthur Lee's accusations. Congress recalled Deane in December 1777 and subsequently charged him with financial impropriety. Unable to adequately defend himself without his records, Deane faced further scandal when intercepted letters suggested pessimism about the American cause, branding him a traitor by some.

Post-war, Deane lived in Europe, primarily in Ghent and London, attempting unsuccessfully to rebuild his fortune and clear his reputation. He authored defenses of his wartime actions but fell into poverty. Deane died under mysterious circumstances aboard the ship Boston Packet on September 23, 1789, possibly poisoned. His descendants eventually secured financial restitution from Congress in 1841, rectifying previous injustices against him.

In March 1776, Deane was appointed as the first American envoy to France, tasked with obtaining crucial financial and military support. He successfully negotiated the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France alongside Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee. Deane recruited notable foreign officers such as Lafayette, von Steuben, and Pulaski, significantly bolstering the American military effort. However, controversy arose over his financial dealings, exacerbated by rival Arthur Lee's accusations. Congress recalled Deane in December 1777 and subsequently charged him with financial impropriety. Unable to adequately defend himself without his records, Deane faced further scandal when intercepted letters suggested pessimism about the American cause, branding him a traitor by some.

Post-war, Deane lived in Europe, primarily in Ghent and London, attempting unsuccessfully to rebuild his fortune and clear his reputation. He authored defenses of his wartime actions but fell into poverty. Deane died under mysterious circumstances aboard the ship Boston Packet on September 23, 1789, possibly poisoned. His descendants eventually secured financial restitution from Congress in 1841, rectifying previous injustices against him.

No Image

John Dickinson

13 Nov 1732 – 14 Feb 1808

Home:

Talbot County, MD

Education:

Home-schooled

Profession:

Lawyer, politician

Info:

John Dickinson, known as the "Penman of the Revolution," was born in 1732 at Crosiadore estate in Maryland. He moved to Delaware with his family in 1740 and later pursued legal studies in Philadelphia and London. Returning to Philadelphia in 1757, he became a prominent lawyer and married Mary Norris in 1770.

Dickinson’s political career began with his election to the Delaware assembly in 1760 and later the Pennsylvania assembly. Despite losing his seat in 1764 due to political conflicts, he emerged as a key figure in the American Revolutionary movement, particularly through his writings against the Stamp Act in 1765 and subsequent publications advocating colonial rights.

His efforts included drafting resolutions for the Stamp Act Congress and penning the influential "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania." Despite his opposition to immediate violent resistance, Dickinson's political and military involvements deepened as relations with Britain deteriorated, leading him to the First Continental Congress and various local defense committees in Philadelphia.

Although Dickinson opposed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, his contributions continued as he helped draft the Articles of Confederation and participated in military service. Later, he served as president of both Delaware and Pennsylvania, attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and supported the U.S. Constitution's ratification. Dickinson spent his final years writing and died in 1808 in Wilmington, Delaware.

Dickinson’s political career began with his election to the Delaware assembly in 1760 and later the Pennsylvania assembly. Despite losing his seat in 1764 due to political conflicts, he emerged as a key figure in the American Revolutionary movement, particularly through his writings against the Stamp Act in 1765 and subsequent publications advocating colonial rights.

His efforts included drafting resolutions for the Stamp Act Congress and penning the influential "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania." Despite his opposition to immediate violent resistance, Dickinson's political and military involvements deepened as relations with Britain deteriorated, leading him to the First Continental Congress and various local defense committees in Philadelphia.

Although Dickinson opposed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, his contributions continued as he helped draft the Articles of Confederation and participated in military service. Later, he served as president of both Delaware and Pennsylvania, attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and supported the U.S. Constitution's ratification. Dickinson spent his final years writing and died in 1808 in Wilmington, Delaware.

James Duane

6 Feb 1733 – 1 Feb 1797

Home:

Education:

Profession:

Info:

James Duane was born on February 6, 1733, in New York City to wealthy parents Anthony Duane and Althea Ketaltas. After his mother's death in 1736 and father's in 1747, he became a ward of Robert Livingston, 3rd Lord of Livingston Manor. He studied law under James Alexander, was admitted to the bar in 1754, and began practicing law in New York City. In 1762, he became clerk of New York’s Chancery Court and served briefly as acting attorney general in 1767. His successful legal practice made him wealthy, owning extensive property in Manhattan and an estate, Duanesburg, in Schenectady County, New York. Duane married Mary Livingston in 1759, strengthening ties to influential political circles.